Roast Duck(Kaoya)

The Beijing roast duck is a dish well-known among gastronomes the world over.

To cook ducks by direct heat dates back at least 1,500 years to the period of the Northern and Southern Dynasties, when "broiled duck" was mentioned in writing. About eight hundred years later, Husihui, imperial dietician to a Mongol emperor of the Yuan Dynasty, listed in his work Essentials of Diet (1330 A. D.) the "grilled duck" as a banquet delicacy. It was made by heating the duck-stuffed with a mince of sheep's tripe, parsley, scallion, and salt-on a charcoal fire.

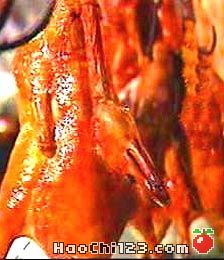

Today the Beijing roast duck (or "Peking duck", as it has been called) is made of a special variety of duck fattened by forced feeding in the suburbs of Beijing. After the duck is drawn and cleaned, air is pumped under the skin to separate it more or less from the flesh. And a mixture of oil, sauce and molasses is coated all over it. Thus, when dried and roasted, the duck will look brilliantly red as if painted. Perhaps that is why it is known among some Westerners as the canard laqué or "lacquered duck."

Before being put in the oven, the inside of the fowl is half filled with hot water, which is not released until the duck has been cooked. For oven fuel, jujube-tree, peach or pear wood is used because these types of firewood emit little smoke and give steady and controllable flames with a faint and pleasant aroma. In the oven, each duck takes about fourty minutes to cook, and the skin becomes crisp while the meat is tender.

In the restaurant, the roast duck, after being shown whole to the customers, is served in slices, which are eaten rolled in thin pancakes with a dish of tianmianjiang (a sweet sauce made of fermented flour) and scallion (or cucumber) cut in thin lengths. Few people, if any, could resist the temptation of the crisp and delicious taste of the Beijing roast duck.

Before the duck appears, however, various warm or cold dishes are often served, made of kidneys, hearts, livers, webs, wings and eggs, all from the duck. Even duck tongues can beprepared into very tasty dishes, and the skeleton of the eaten duck normally goes into a soup which finds few equals. A highly experienced chef of a duck restaurant can produce an "all-duck banquet" of over eighty dishes made of different parts of the fowl.